Technological University Dublin

ARROW@TU Dublin

Dissertations Social Sciences

2019

“The Zero to Three Years are so Important” An Exploration of the Needs of Young Children in ECEC Settings from a Policy and Practice Perspective.

Rosemary Brien

Technological University Dublin

Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/aaschssldis

Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons

Recommended Citation

Brien, R. (2019)“The Zero to Three Years are so Important” An Exploration of the Needs of Young Children in ECEC Settings from a Policy and Practice Perspective.Dissertation, Technological University Dublin.

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Social Sciences at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected].

TU Dublin – City Campus Online Dissertation Copyright Policy

The TU Dublin City Campus Library Online Dissertation Collection is comprised of undergraduate and postgraduate taught dissertations.

The copyright of a dissertation resides with the author. All TU Dublin students are bound to comply with Irish copyright legislation during their course of study. A dissertation is made available for consultation on the understanding that the reader will not publish it in any form, either the whole or any other part of it, without the written permission of the author.

To learn more about copyright and how it applies to you click here:

The Online Dissertation Collection is only available to be accessed by registered TU Dublin City Campus staff and students. Non-members of TU Dublin cannot be given access to the Online Dissertation Collection. (Please note that this also applies to graduates of TU Dublin and graduates of the former Dublin Institute of Technology requiring a copy of their own work). In using the Online Dissertation Collection students should be fully aware of the following points:

• Usernames and passwords are for personal use only. They must not be divulged for use by any other person.

• The Online Dissertation Collection is provided for personal educational purposes to support you in your courses of study. Use of this collection does not extend to any non-educational or commercial purpose.

• You must not email copies of any dissertation or print out copies for anyone else. You must not under any circumstances post content on bulletin boards, discussion groups or intranets etc.

• You must not remove, obscure or alter in any way any copyright information or watermarks that appear on any material that you download/print from the collection

TU Dublin City Campus Library has to right to temporarily or permanently remove a digitised dissertation from the collection.

“The Zero to Three Years are so Important” An Exploration of the Needs of Young Children in ECEC Settings from a Policy and Practice Perspective.

Rosemary Brien (BA Early Childhood Care and Education).

Declaration of ownership: I declare that the attached work is entirely my own and that all sources have been acknowledged.

Signature:

Submitted to the Department of Social Sciences, Technological University Dublin, in partial fulfilment of the requirements leading to the award Masters (MA) in Mentoring, Management and Leadership in the Early Years.

Word Count: 13,993

Technological University Dublin April 2019

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to sincerely thank the individuals who participated in the interviews for this research study for very generously giving time and energy out of their busy days. This research would not have been possible without their great insight into this topic.

I would also like to thank my supervisor, Emma Byrne-MacNamee for her invaluable advice and support throughout this process and for providing her expert guidance.

I am extremely grateful to my family and friends for their understanding, patience and when necessary, distraction.

Special thanks to my husband who has been a calm, steady and patient support throughout this entire process.

I would like to dedicate this research to my children who were the driving force behind this study.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Declaration

Acknowledgements

Table of Contents

List of Tables and Figures

Abbreviations

Glossary of Terms

Abstract

1 Chapter One Introduction ………………………………………………………………………

Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………

Aims of the Study ………………………………………………………………………………

Rationale for the Study ……………………………………………………………………….

Research Methodology ……………………………………………………………………….

Organisation of Chapters …………………………………………………………………….

2 Chapter Two Literature Review ……………………………………………………………..

Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………

Theoretical Framework ………………………………………………………………………

The Needs of Young Children ……………………………………………………………..

The Early Years Workforce…………………………………………………………………

ECEC in Ireland ………………………………………………………………………………

Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………………

3 Chapter Three Methodology …………………………………………………………………

Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………….

Research Design ………………………………………………………………………………

Research Instrument …………………………………………………………………………

Sample ……………………………………………………………………………………………

Research Methods ……………………………………………………………………………

Limitations of the Study ……………………………………………………………………

Data Analysis ………………………………………………………………………………….

Ethical Considerations ………………………………………………………………………

Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………………

4 Chapter Four Findings …………………………………………………………………………

Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………….

Profile of Settings …………………………………………………………………………….

The Needs of Young Children ……………………………………………………………

Qualifications and Training ……………………………………………………………….

Perspectives on Policy and Practice ……………………………………………………

Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………………

5 Chapter Five Discussion and Conclusion ……………………………………………….

Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………….

The Needs of Young Children ……………………………………………………………

Qualifications and Training ……………………………………………………………….

Perspectives on Policy and Practice ……………………………………………………

Recommendations ……………………………………………………………………………

Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………………

References

Appendices

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

Table 1 Profile of ECEC Settings

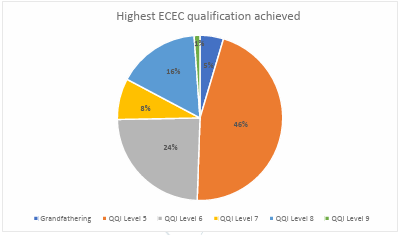

Figure 1 Highest ECEC qualification achieved by practitioners

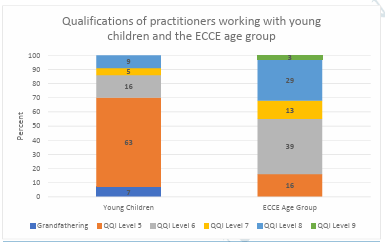

Figure 2 Qualifications of practitioners working with young children

and the ECCE age group

ABBREVIATIONS

ACS Affordable Childcare Scheme

AIM Access and Inclusion Model

CCS Community Childcare Subvention Programme

CCSU Community Childcare Subvention Universal Programme

CPD Continuous Professional Development

DCYA Department of Children and Youth Affairs

ECCE Early Childhood Care and Education Programme

ECEC Early Childhood Education and Care- an umbrella term used to describe any and all services for children from birth to six years.

QDS Better Start Quality Development Service

QQI Quality and Qualifications Ireland

TEC Training and Employment Childcare Programme

ZPD Zone of Proximal Development

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

For the purposes of this study, the following terms are defined as follows:

Practitioner A person working in a service for children from birth to six years.

Young Children Throughout this work, this term refers to children under the age of 2 years 8 months who are not taking part in the Early Childhood Education and Care programme.

ABSTRACT

A strong body of evidence demonstrates that young children under the age of three are experiencing a critical period in their development which impacts long term mental and physical health. Responsive, secure and positive relationships between young children and their caregivers is integral to healthy social and emotional development. The principle aim of this study is to explore how the needs of children under the age of three are perceived and addressed in Irish early childhood education and care settings from a practice and policy perspective.

A qualitative research approach was adopted utilising semi-structured interviews with managers of full day care settings as well as a documentary review of the learning outcomes of the Quality and Qualifications Ireland Level 5 Early Childhood Education and Care award.

The principal findings which emerge from this study show that a greater percentage of less qualified and unqualified practitioners, are working with the younger age group and the question as to whether these practitioners are likely to be less effective at meeting the very specific needs of young children is raised. Findings also indicate that current policy, which requires a lower qualification and contributes to poorer working conditions for practitioners may be directly, negatively affecting the quality of the early care and education of young children.

1 Chapter One Introduction

1.1 Introduction

This study explores the perspectives of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) managers of full day care settings in relation to the needs of young children from a policy and practice context. This chapter will introduce this research by outlining the aims of the study, the rationale for the research and the methodology employed. It will conclude with an outline of the study.

1.2 Aims of the Study

The overall aim of this study is to explore the needs of young children in ECEC settings from a policy and practice perspective. The key objectives are to explore ECEC managers understandings of the needs of young children, their views on current qualification requirements for children from 0-6 years of age and their perspectives on the influence and impact on practice of current policy.

1.3 Rationale for the Study

The purpose of this research is to ascertain the perspectives of managers of full day care ECEC settings on how the needs of young children are perceived and addressed relevant to qualifications and training, and policy and practice. Currently, a significant proportion of ECEC funding from the Department of Children and Youth Affairs (DCYA) is targeted at the Early Childhood Care and Education Programme (ECCE). This provides a universal entitlement of fifteen hours of ECEC per week for all children from the age of two years eight months until they begin primary school (DCYA, 2018). Early years settings receive a subsidy for eligible children where the preschool leader is qualified to Quality and Qualification Ireland (QQI) Level 6. Settings with practitioners qualified to QQI Level 7 or higher receive a greater subsidy. The minimum qualification requirement for the ECEC sector is a QQI Level 5 award. The introduction of the ECCE programme has led to more highly qualified practitioners working with the older age group in order to meet the requirements of this programme. This results in less qualified and unqualified practitioners working with young children. Young children have been shown to be experiencing a critical period of development. Central to providing high quality ECEC for this age group are well trained practitioners who understand their needs and crucially, how to meet these needs. More highly qualified practitioners have been shown to display a more positive attitude towards young children and are more able to provide a high quality pedagogic programme for children (OCED, 2006; Dalli, White, Rockel, Duhn, Buchanan, Davidson, Ganly, Kus, & Wang, 2011; OECD, 2012; Mathers, Eisenstadt, Sylva, Soukakou, & Ereky-Stevens, 2014; French, 2018).

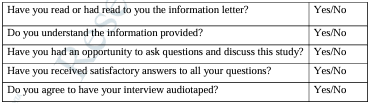

1.4 Research Methodology

The methodological approach for this research is a qualitative approach using semi structured interviews as the main research instrument. The second research method employed is documentary research relating to the learning outcomes of the QQI Level 5 training modules. A qualitative approach was chosen for this study as it lends itself to providing an exploratory insight into the experiences, understandings, attitudes and values of the research participants (Denscombe, 2017; Creswell & Creswell, 2018). The research sample for the semi-structured interviews was made up of nine managers from eight full day care settings. These managers were purposively selected on the basis of the services they offer to young children. This research complied with the ethical guidelines set out by Technological University Dublin (TUD) (2019). Participants were made aware of the purpose of the research and were guaranteed confidentiality and full anonymity.

1.5 Organisation of Chapters

Chapter 2 provides an overview of the theoretical framework which informs this research study. Following this, the relevant literature will be reviewed, beginning with the needs of young children, the competences of the workforce necessary to meet these needs and the role of the ECEC manager. The evolution of the Irish ECEC system will be examined and current practice and policy will be reviewed.

Chapter 3 outlines the research methods employed for this study along with a rationale for these methods. How the data was analysed will be outlined including a short reflexive piece by the researcher. The ethical considerations for this research conclude this chapter.

Chapter 4 presents the main findings from this research. These are outlined under the main headings of the needs of young children, qualifications and training and, perspectives on policy and practice.

Chapter 5 discusses the findings outlined in Chapter 4 in the context of the literature review with regard to the aims and objectives of the study. This chapter makes recommendations which are drawn from the findings and offers a conclusion to this study.

2 Chapter Two Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

Young children have been shown to be experiencing a critical period in their development that is sensitive to the relationships they experience (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000). Their needs differ from those of their older peers and central to providing high quality ECEC for this age group are well trained practitioners who understand those needs (Dalli et al., 2011).

This chapter will summarise the main themes from the literature, relevant to policy and practice, relating to young children in ECEC. The theoretical perspectives considered central to this research, those of Erikson, Bowlby, Vygotsky and Bronfenbrenner will be reviewed in terms of their relevance to quality ECEC experiences for young children. The theoretical framework will be explored followed by an analysis of what constitutes quality ECEC for young children. Literature in relation to the specific needs of young children will be presented followed by a review of competences of the adult necessary for working with young children and the role of the ECEC manager in this regard. The development and evolution of the Irish ECEC system will be examined and evidence of policy and practice trends will also be presented.

2.2 Theoretical Framework

This research will draw on the theoretical perspectives of Erikson, Bowlby, Vygotsky and Bronfenbrenner given their relevance to the critical period of development of children from birth to three years of age.

2.2.1 Developmental perspective.

Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development asserts that individuals move through eight stages of development with mastery of each stage linked to specific experiences and to healthy development (Erikson, 1995; Nutbrown & Clough, 2014). The first stage of development, according to Erikson, takes place from birth to eighteen months. Mastery of this stage brings with it an enduring sense of confidence and trust in the self, others and the future (Erikson, 1995; Poole & Snarey, 2011). This stage is closely linked to the formation of attachment and is supported by John Bowlby’s (1998) theory of attachment. Bowlby’s theory states that children need secure, consistent and trusting relationships with responsive adults who know them well in order to thrive (Bowlby, 1977). Infants who experience sensitive and responsive relationships with a primary caregiver develop healthy attachment behaviours and build trust in their own abilities and in others to have their needs met (Erikson, 1995; Mooney, 2000). Erikson describes the second stage of development as one which is characterised by a conflict between the child’s developing sense of autonomy and self-doubt and shame which occurs from the age of eighteen months to three years. The child who successfully masters this stage will acquire a strong sense of self and personal control. To support the development of a strong sense of independence, toddlers must be given opportunities for choice and control (Erikson, 1995; Mooney, 2000).

Both Erikson and Bowlby stress the importance of early experiences as being formative and having a powerful effect on later development. Developmental theories of childhood, such as these, stress this stage of life as being universal and this view of child development has dominated and influenced ECEC studies and practice (Morgan, 2011; Prout & James, 2015). Erikson’s and Bowlby’s theories demonstrate that infants need sensitive and responsive relationships with a primary caregiver and toddlers need to be given opportunities for choice and control in order to help them develop trust and independence. This developmental approach has its detractors (Prout & James, 2015; Walsh, 2005; Woodhead, 2006) on the basis that it does not take into consideration how children learn and grow in different social contexts and the nuances of children’s interactions with the people and places around them. The literature that will be reviewed for the purposes of this research will focus on the specific needs of young children and how these needs are best met.

2.2.2 Sociocultural perspective.

Lev Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of child development is one of the foundations of social constructivism which proposes that personal and social experience cannot be separated, and knowledge is constructed through interaction with others (Vygotsky, 1980). Vygotsky proposes that social interaction is a core and fundamental element of cognitive development. This theory emphasises the importance of the child’s interactions with caregivers to further children’s knowledge, with language being essential to cognitive development (Morgan, 2011). Vygotsky devised the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which refers to the difference between what a child can do independently and what they are capable of doing with the assistance of a more knowledgeable other. The ZPD is the area which requires the most sensitive adult guidance to enable “scaffolding” (Vygotsky, 1978; Hedegaard, 2005). Scaffolding requires the adult to carefully observe the young child to determine their emerging interests and plan a programme of ECEC which challenges their competence (Morgan, 2011). From another perspective, Rogoff (1990) holds that Vygotsky’s work is not culturally universal and asserts that the concept of scaffolding, which is dependent on verbal interaction, may not be relevant in all cultures and for all types of learning.

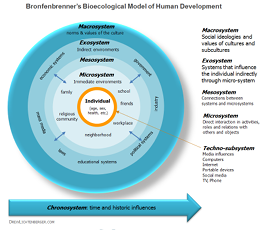

Uri Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model of development was influenced by the work of Vygotsky. Bronfenbrenner’s theory proposes that interactions between the child and their environment influence development over time. Bronfenbrenner categorised the environments the child interacts with into a nested system of contexts with the child placed at the centre of these systems (Appendix 1). The child and their personal characteristics play an active role in their development which occurs through interactions with each of these contexts over time (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994). Central to this research are the exosystem and macrosystem contexts. The exosystem includes settings that influence the child’s development but in which the child may not have an active role, such as Government, where policy influences the child’s experiences of ECEC. The macrosystem relates to influences that take place at a cultural level such as the dominant political view on childhood and how ECEC is resourced (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Hayes, O’Toole & Halpenny, 2017).

Bronfenbrenner’s theory recognises the importance of understanding how the child’s immediate environment as well as the broader cultural setting influence their development and how the child influences these contexts through interaction. This theory has been criticised for its depiction of development within a nested system. Neal and Neal (2013) suggest that the nested systems would be better described as networked which would more accurately reflect the way the systems relate to one another and overlap. The relevance of Bronfenbrenner’s theory to this research is that it allows for an analysis of how government policy and the dominant political view on childhood influence the experiences of the child in ECEC. This will be reflected in the literature that will be reviewed.

2.3 The Needs of Young Children

2.3.1 Evidence from neuroscience.

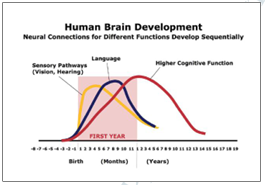

The period up to three years of age is a critical time for optimal brain development. The brain doubles in size in the first year of life and will reach 80% of its adult volume by the age of three (Gerhardt, 2005). New evidence from neuroscience proposes that while genes form the blueprint for the developing brain, environmental factors are also central in determining how the neural circuitry of the brain develops (Shonkoff & Fisher, 2013). This means that nurture and nature are critical, and highlights the significance of early experiences on brain development (Herrod, 2007). Brain development up to the age of three affects long term mental and physical health and early experiences, including relationships with caregivers, have been shown to interplay with genes to help shape brain formation (Nugent, 2005). A major predictor of effective brain development and social emotional functioning has been found to be caregiver responsiveness and sensitivity of care for young children (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000; Perry, 2002; Sroufe, 2005). Neuroscience, therefore, recognises the importance of responsive, secure and positive relationships between young children and their caregivers for healthy social and emotional development. Appendix 2 illustrates how the first three years of life are a critical period for brain development.

2.3.2 Importance of quality.

Given the importance of this critical period for brain development, the provision of high quality ECEC is imperative (Urban, Vandenbroeck, Van Laere, Lazzari, & Peeters, 2011; French, 2018). In fact, it has been shown that poor quality ECEC can be worse for young children than no ECEC (Sylva, Melhuish, Sammons, Siraj-Blatchford & Taggart, 2004; French, 2018). Children’s outcomes from ECEC are dependent on the quality of the setting. The assessment of quality can be understood in relation to process and structural quality. Process quality relates to the child’s experiences in the setting and involves social, emotional and physical interactions. Structural quality relates to regulable factors, that can be addressed in policy, such as group size, adult child ratios and practitioner training.

Structural quality is an important precondition for process quality (Campbell-Barr & Leeson, 2016; OECD, 2018). It should be noted that quality is, however, a constructed concept based on the dominant cultural values and beliefs and perspective on childhood within a society (Dahlberg, Moss & Pence, 2007). Wenger (1998) cautions that practice, and indeed what constitutes quality, can often become taken for granted with complex theories and meanings becoming simplified and remaining unquestioned. There is, nevertheless, consensus from current western research on the aspects of provision that have a positive impact on the quality of ECEC for young children.

Mathers et al., (2014) have identified several aspects of process quality central to providing high quality ECEC. Young children benefit from stable relationships and interactions with sensitive, responsive adults; they need support in developing their communication and language abilities; they need opportunities to move and be physically active and to take part in play based activities and routines where they can take the lead in their own learning. There are several elements of structural quality that assist in providing these aspects of process quality. Research by Ahnert, Pinquart, & Lamb (2006), Dalli et al. (2011), Melhuish, Ereky-Stevens, Petrogiannis, Ariescu, Penderi, Rentzou, Tawell, Leseman & Broekhuisen (2015) and French (2018) has found that adult child ratios of 1:3 are considered optimal for young children, as are small group sizes of six to eight children. Along with caregiver sensitivity, these elements have been shown to have positive implications for the formation of attachment. Central to ensuring high quality ECEC are well trained practitioners, who understand the needs of young children and how to meet these needs. More highly qualified practitioners have been shown to display a more positive attitude towards young children (OCED, 2006; Dalli et al., 2011; Mathers et al., 2014; French, 2018).

Higher qualifications and continuous professional development (CPD) contribute to higher quality as adults are more capable of providing warm, supportive and stimulating interactions with children (OECD, 2006; Dalli et al., 2011). Young children require low stress environments as they are linked to healthy brain development (Dalli et al., 2011). Low stress environments can be achieved through the structural quality measures mentioned, as lower ratios and group sizes offer better working conditions for practitioners which lead to job satisfaction and reduced stress (OECD, 2006; Dalli et al., 2011). The components of structural quality described are all elements that can be addressed in policy and the introduction of these elements can improve process quality, or interactions, for young children.

2.4 The Early Years Workforce

2.4.1 Core competences of the workforce.

Given what is known about the critical phase of development that is the period up to three years of age it is imperative that those working with young children are equipped with the specialist knowledge, skills and competences required to provide high quality ECEC. Young children have a specific set of needs that must be met through ECEC to ensure optimum development. Research recommends that at least 60% of the ECEC workforce be trained to bachelor’s degree level. Practitioners educated to this level have been shown to be more competent in providing high quality pedagogy with the competences of the workforce being a significant predictor of quality (Urban et al., 2011). First Five: A Whole-of-Government Strategy for Babies, Young Children and their Families 2019-2028 (Government of Ireland, 2018) provides a commitment to a graduate led workforce of 50% by 2028 with an initial target of 30% by 2021.

Several key characteristics of practitioners working with young children have been identified. Practitioners should be skilled in intersubjectivity, this is where the child and adult are communicating and interacting in balance with one another. This promotes the child’s capacity to learn (Dalli et al., 2011; French, 2018). Initial training and CPD that is specific to how young children learn and emphasises intersubjectivity is essential to allow adults to employ the specialised practices necessary to provide quality ECEC (Dalli et al., 2011). Practitioners must be knowledgeable about contemporary theories of child development, including neuroscience and through careful observation of the child, should develop a curriculum appropriate to the child’s context (Hayes, 2007; Dalli et al., 2011; Urban et al., 2011). Adults who are skilled in reflexive practices and who can interpret and respond to the subtle cues of young children are better equipped to provide quality ECEC experiences (Hayes, 2007; Dalli et al., 2011; Urban et al., 2011; French, 2018). Initial training is key to educating practitioners on how to provide quality ECEC for young children. Chazan-Cohen, Vallotton, Harewood & Buell (2017) caution that there is a danger that content on young children in ECEC courses can be sparse. They note that young children are seen as less competent than their older peers rather than children going through a critical period of development that requires specific competences from the adults working with them. This raises the importance of CPD and mentoring for practitioners placed with young children as these measures have been shown to positively influence quality (Urban et al., 2011; Chazan-Cohen et al., 2017).

2.4.2 The role of the ECEC manager.

One of the roles of the ECEC manager is to provide pedagogical leadership for practitioners working with young children. This involves the development and improvement of educational practices (Hujala & Eskelinen, 2013). The quality of pedagogical leadership is strongly linked to the leader’s education level and professional development. Research has found that practitioner quality is maintained by strong leadership (Sylva et al., 2004; Aubrey, 2011; Rodd, 2013). Research by Fonsen (2013) finds that ECEC leaders must be knowledgeable regarding pedagogy in order to be effective pedagogical leaders, but Stamopoulos (2012) cautions that leadership responsibilities imposed on those in ECEC are often far beyond the scope of their professional training and expertise. Until 2016 there was no requirement for the ECEC manager in Ireland to have a qualification of any description. Managers must now meet the minimum qualification requirement of a QQI Level 5 ECEC award. This is in contrast to other jurisdictions, such as Norway, where in 2005 the state decided to professionalise the sector and introduced a requirement for all managers and pedagogical leaders to be qualified to degree level in ECEC (Moloney & Pettersen, 2017).

The ECEC manager is all things to all people and holds accountability to children, families, practitioners and local and national stakeholders. Their work is impacted by top down initiatives from national stakeholders, such as government funding programmes (Campbell-Barr & Leeson, 2016). This accountability requires leaders to manage and balance competing workloads on a daily basis which can hinder their ability to provide pedagogical leadership (Hujala & Eskelinen, 2013; Campbell-Barr & Leeson, 2016).

Policy recognises that strong leadership and appropriate organisational structures are central to providing high quality, effective services for children. Through a new workforce development plan, Government plans to establish a career framework and leadership development opportunities, which are currently sparse, for the ECEC workforce (DCYA, 2014; Government of Ireland, 2018). In order to support this professionalisation, research recommends that successful workforce development requires top down input from government, and leadership is required from both the individual practitioner and a supportive policy infrastructure (Georgeson, Campbell Barr, Mathers, Boag-Munroe, Parker-Rees & Caruso, 2014; Dalli, 2017). Dalli (2017) notes that professionalisation requires leadership, in particular, to advocate for the specialist nature of ECEC for young children.

2.5 ECEC in Ireland

2.5.1 Background.

The introduction of the Child Care Act (1991) led to a reform of the ECEC sector which, until then, had consisted of informal provision. Coupled with this, increasing numbers of women began working outside the home and a growth in the economy led to a demand for ECEC (Share, Corcoran, & Conway, 2012). A number of funding programmes were introduced, which by 2010 had seen an additional 70,000 ECEC places created, with the principal aim of facilitating parents, primarily women, to join the labour force (DJELR, 2004; OMC, 2007; Hayes, 2010).

In response to an exposé of poor practice in ECEC settings for young children on national television in 2013 entitled “Breach of Trust”, several measures aimed at improving the quality of ECEC were introduced (Moloney, 2014). This included the introduction of a minimum qualification requirement for the workforce at QQI Level

5 (DCYA, 2016). A mentoring programme, Better Start Quality Development Service (QDS), was established for full day care settings. Early Years Education-focused Inspections (EYEI) commenced for settings taking part in the ECCE programme despite the children who were affected in the exposé being from the younger age group (DES, 2016). This demonstrates that the ECEC sector developed from a focus on the economic and political motivations of increasing labour market participation and meeting working parents’ demands for ECEC provision (Adshead & Neylon, 2008). This remained the main focus of ECEC policy until the exposé of poor practice for young children in 2013.

2.5.1.1 Outcomes versus experiences debate.

Investment in ECEC from a political and economic perspective is outcome based and values children for what they will become in the future. Hayes & Bradley (2009) note that an emphasis on economic policies undermines the rights of children to quality ECEC. This investment is in contrast to the principles of Aistear: The Early Childhood Curriculum Framework (NCCA, 2009) and Síolta: The National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education (DES, 2017) which view childhood as a specific stage of life. One that requires adequate funding and resources to respect the rights of children and meet their needs. Central to this concept is that childhood should be valued as a unique stage of being.

The Swedish model of ECEC shares similar origins to that of the Irish system. It emerged from a period of rapid industrialisation which created a demand for labour market participation and a need for women to join the workforce. In contrast to Ireland, however, Sweden has invested in ECEC to create a system that meets the needs of working parents and is based on the child’s entitlement to ECEC. Sweden has developed a system that is widely regarded as being one of the best in the world with positive outcomes for both children and families (Lamb & Sternberg, 1992; Start Strong, 2013). The Swedish model demonstrates how sociocultural beliefs about the child’s right to quality ECEC, along with the economic goal of increasing labour market participation, can impact positively on children and meet the needs of families.

2.5.1.2 Education versus care in the Irish system.

The ECEC sector also places a focus on preparing children for formal education. The DCYA (2018) state that the ECCE programme offers children their first formal experience of early learning before primary school. The perceived “schoolification” of ECEC is a contributing factor to the dichotomy of education and care with greater investment and higher qualification requirements placed on provision for children over three (Moss, 2008; Moss & Cameron, 2011; Van Laere, Peeters & Vandenbroeck, 2012). This emphasis on education is connected to the economic and political perspective as it is seen as a means to improve human capital and increase future returns on investment (Start Strong, 2013).

Another contributing factor to the division between education and care is the dominant sociocultural belief regarding ECEC and how this influences investment. Irish ECEC has historically received low public investment and is based on a mixed market model of informal and private, for profit, providers (Hayes, 2007; Moss, 2008; UNESCO, 2010). The care of young children has generally been viewed as a private responsibility for the family with policies targeted as welfare measures to ameliorate social issues. Care is viewed as a service and a soft skill linked to mothering and what women naturally do which does not require specific training (Hayes, 2007; Moss, 2008; & Van Laere et al., 2012).

2.5.2 Contemporary policy context.

2.5.2.1 Qualification requirements.

At the time of the exposé of poor practice in 2013, there were no qualification requirements for ECEC practitioners. Minimum qualification requirements at QQI Level 5 were introduced for the sector in December 2016 in response to this exposé (DCYA, 2016). Practitioners with no qualification were given the option of signing a grandfathering declaration which allows them to continue to work in ECEC provided they leave the sector by 2021 (Pobal, 2018). In their annual ECEC sector profile, Pobal (2018) report that young children are more likely to have lower qualified practitioners, at QQI Levels 5 or 6, placed in charge of their care and education, with the most qualified practitioners more likely to be working with children over three years of age.

2.5.2.2 Funding programmes.

Currently, there are two universal funding programmes delivered by the DCYA. The Community Childcare Subvention Universal (CCSU) programme offers a subsidy of up to €20 per week for children from the age of six months until they enter the ECCE programme (DCYA, 2018). The ECCE programme provides a universal entitlement of fifteen hours of ECEC per week over 38 weeks of the year for all children from the age of two years eight months until they begin primary school. Participating ECEC settings receive a subsidy of €69 for each eligible child where the preschool leader is qualified to QQI Level 6. Settings with practitioners qualified to QQI Level 7 or higher receive a greater subsidy of €80.25 for each eligible child (DCYA, 2018).

However, young children can avail of subsidy of up to €145 per week for full time ECEC as part of the targeted Community Childcare Subvention (CCS) programme for disadvantaged families and the Training and Employment Childcare (TEC) programme for parents taking part in further education or those returning to employment. The DCYA are in the process of introducing the Affordable Childcare Scheme (ACS) which will replace the CCS and TEC programmes and will see children from six months to fifteen years provided with a subsidised place determined by family income (Government of Ireland, 2018). The Access and Inclusion Model (AIM) offers support for children with additional needs who are taking part in the ECCE programme (DCYA, 2018).

2.5.2.3 Parental arrangements.

Paid maternity leave is provided for a period of 26 weeks with an option to take a further 16 weeks unpaid leave. Paid paternity leave, introduced in 2018, is provided for a period of two weeks. Unpaid parental leave is available for a maximum of 18 working weeks and until the child turns eight (DEASP, 2018a; French, 2018). Two weeks paid parental leave to be taken in the child’s first year was announced in 2018 to come into effect in 2019 (DEASP, 2018b). The First Five Strategy sets out a plan to develop a more generous parental leave system by 2028, which along with paid maternity leave, will allow parents to stay at home with their infant until one year of age (Government of Ireland, 2018).

In Sweden, on the contrary, there is an entitlement to 480 days or 16 months of paid parental leave, available until the child turns eight, with each parent having an exclusive right to 90 of these days. For 390 of these days parents are paid at 80% of their earnings with the remaining days paid at a flat rate (Hagqvist, Nordenmark, Pérez, Trujillo Alemán & Gillander Gådin, 2017; Swedish Institute, 2019). Research by Russell, Watson, & Banks (2011) and Moss (2012) argues that parental leave and entitlements to ECEC should be seamless in order to be effective. Otherwise, parents may be unable to afford to take unpaid leave or the ECEC provision offered will not meet the needs of working parents.

2.6 Conclusion

Historically, Irish ECEC policy has suffered from a fragmented approach to policy development with investment motivated by economic and political motivations to improve labour market participation. Progress has been made in recent years in placing the child at the centre of ECEC, but young children are currently more disadvantaged than their older peers in terms of funding and practitioner qualifications.

The literature demonstrates that young children have a very specific set of needs due to the critical period of development they are experiencing. They need supportive, responsive interactions with adults who are attuned to their needs. These adults must have a thorough understanding of child development related to this age group and be aware of how and why specialised ECEC is important. The ECEC manager is key to supporting practitioners in this regard. These measures can be supported through structural quality which can be addressed through policy.

This research will explore these themes as they are reflected in current policy and practice for young children in Ireland through a social constructivism lens. The research will build on the existing literature regarding meeting the needs of young children through policy and practice by examining the interaction of these elements in the provision of ECEC for young children. The following chapter will discuss the methodological details of how this research study was conducted.

3 Chapter Three Methodology

3.1 Introduction

The overall aim of this study is to explore the needs of young children in ECEC settings from a policy and practice perspective. The research objectives focus on investigating the perspectives of ECEC managers on a number of key issues. These include the needs of young children, the impact of current policy relating to working with young children; and the implications of current qualification requirements for practitioners working with children under six years of age.

The following chapter seeks to provide an overview of the research design for this study, including a description of the research methods employed. Details of the research sample, how participants were selected, and the profile of the final sample will be outlined. The limitations of the study and relevant ethical considerations will be discussed. An overview of the process of collecting, reviewing and analysing data will be set out.

3.2 Research Design

The research paradigm that guides this study is interpretivism. This epistemological approach relates to how individuals construct meaning as they interact with and interpret their world based on their social perspectives (Patton, 1990; Creswell & Creswell, 2018). This paradigm also recognises that the researchers own background, experiences and identity shape how the data collected is interpreted (Denscombe, 2017; Creswell & Creswell, 2018). The interpretivist paradigm is associated with flexible research designs, such as phenomenology which has been chosen for this study. Phenomenology deals with people’s perceptions, feelings, attitudes and beliefs and how they construct their social reality (Denscombe, 2017). Interpretivism, therefore, employs a constructivist ontological position where the social world is the outcome of interactions between individuals (Bryman, 2016). This concept has been detailed previously in the literature review as central to meeting the needs of young children. It is critical, therefore, that the research design reflects this concept.

The research design that best suits this study is a small scale qualitative approach using semi-structured interviews. Denzin and Lincoln (2000) define qualitative research as involving an interpretive approach to the subject matter whereby the researcher attempts to make sense of phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Qualitative research lends itself to an exploratory insight into the research participant’s experiences, understandings, behaviours, attitudes and values (Denscombe, 2017; Creswell & Creswell, 2018). This paradigm has been chosen as managers perspectives on policy and practice relating to young children will vary and this methodological approach will allow for a richness of detail to be drawn from each participant’s experiences. Knowledge and understanding of current policy and practice is constructed through engagement with these aspects of ECEC, therefore, the interpretivist paradigm will allow the research to reflect this.

A post positivist approach to research design was deemed inappropriate for this study. In order to answer the research questions, it was regarded as necessary to obtain information on the experiences and perspectives of managers relating to current policy and practice for young children. This would not be possible through post positivist quantitative data collection methods which deal with the collection and analysis of statistical data (Bryman, 2016).

3.3 Research Instrument

The chosen research instrument must enable the researcher to gather evidence and information on the topic which is reliable, measurable and transferable (Denscombe, 2017). Two research instruments were chosen for this study. Semi-structured interviews were used with managers of full day care ECEC settings. The second research instrument employed was documentary research relating to the learning outcomes of the QQI Level 5 ECEC training modules.

Semi-structured interviews allow the researcher to gain insight into people’s opinions, feelings, experiences, attitudes and values on the research topic. More specifically, they allow the research participant to develop ideas and speak more widely on issues raised by the researcher (Denscombe, 2017). Comparability of responses is a strength of this method as participants are asked the same core questions (Appendix 4) (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2011). This methodological approach was chosen as it allows for a richness and depth of detail to be drawn from the participants’ reflections on current policy and practice relating to young children.

There are a number of advantages to documentary research, access to data is relatively easy and cost effective and information contained within these sources is permanent and open to public scrutiny (Denscombe ,2017). This approach was chosen as it allows for an investigation into the learning outcomes of QQI Level 5 training for the ECEC workforce specific to working with young children.

The researcher is also a significant research instrument as their own background, experiences and identity shape the design, collection and interpretation of the data (Denscombe, 2017; Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

3.4 Sample

This research is based on a small scale study utilising non-probability purposive sampling, the aim of which is to produce an exploratory sample, rather than a sample that is representative of the wider population (Denscombe, 2017). Purposive sampling allows the researcher to select participants based on their detailed knowledge and experience on the research topic in order to provide quality information and insights (Bryman, 2016; Denscombe, 2017). This approach to sample selection was regarded as the most effective means of gathering reliable information for this qualitative, exploratory study.

Managers of a range of full day care ECEC settings were targeted on the basis of the services they offer to young children. It was initially planned to include both private and community settings to ascertain if and how current policy and practice may particularly impact on young children who are considered socio-economically disadvantaged. However, in the selected location, there is only one community, not for profit, setting offering ECEC to young children. This service was included in the sample and the remaining seven interviews took place with private, for profit settings, ranging from large full day care to smaller settings.

3.4.1 Recruitment of research participants.

Through the researcher’s role in an ECEC support organisation, a cross section of full day care ECEC managers were approached to take part in this research. Managers were contacted by the researcher informing them of the background to the study (Appendix 3). The researcher has a positive working relationship with all participants and access to participants was not an issue. Interviews were scheduled at a time and place that was convenient to each participant.

3.4.2 Profile of participants.

A total of nine ECEC managers participated in eight semi-structured interviews, as there were two ECEC managers present during interview five. This comprised eight managers of private ECEC settings and one manager of a community, not for profit, ECEC setting located in an area of disadvantage. All research participants were female. Two of the managers were qualified to QQI Level 5 in ECEC, three to QQI Level 6, two to QQI Level 7 and two to QQI Level 8.

3.5 Research Methods

3.5.1 Pilot interview.

A pilot interview was carried out with a manager of a full day care setting to test the efficacy of the interview questions. This process assists in ensuring the reliability of the research instrument (Denscombe, 2017). This allowed the researcher to make changes to the structure and order of the interview questions. Following this pilot interview, additional questions were added regarding the needs of young children in ECEC.

3.5.2 Research process.

Procedures such as sampling, piloting and informed consent add to the validity of the research method and provide for increased reliability of the research (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Letters containing information on the background of the study were sent to all participants (Appendix 3). An informed consent form (Appendix 5) was completed and signed by all participants and the researcher before each interview. All interviews were audio-recorded, and participants were made aware of this before agreeing to take part in the research. The researcher took field notes both during and after each interview. This process allows the researcher to detail any descriptive information or nonverbal communication which can assist in the interpretation of the data (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). All interviews were fully transcribed with the use of field notes.

3.6 Limitations of the Study

There are a number of limitations to this study. Firstly, it would have been preferable to have a broader perspective from the community sector, as children who attend community ECEC settings may be experiencing more vulnerability and stress due to their family circumstances. However, there was only one community full day care ECEC setting in the area where this research was located. As such, the research was limited by the geographical area. Secondly, as the researcher is an employee in an ECEC support organisation, managing potential bias is an issue as the researcher is immersed in the area of ECEC policy in their employment. Further to this, the researcher has a working relationship with all the interview participants, and this may affect how the questions were framed and answered by participants and therefore, the reliability of the data.

The researcher’s identity may influence the responses of the interviewee, what Denscombe (2017) describes as the interviewer effect. This can be ameliorated by the researcher who is punctual, polite and neutral, thereby creating an environment where the interviewee feels comfortable and is more likely to provide honest responses. Fourthly, this research was limited to female managers as there are no male full day care ECEC managers in the area where the research was conducted. This is representative of the sector with which consists of a female workforce of 98% (Pobal, 2018). Finally, the sample size was small and does not allow for findings to be generalised as they may not be representative of the views of the wider ECEC sector. However, the findings will be useful in generating further research questions relevant to policy and practice for young children.

3.7 Data Analysis

The data analysis approach employed for the semi-structured interviews is thematic analysis which is common to qualitative studies. This method is used to identify, analyse and report patterns or themes and provides a flexible research tool which gives a rich and detailed account of the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). All interviews were transcribed, and each interview was assessed separately and then in relation to each other. ECEC settings were coded using Setting 1 and were abbreviated to S1, S2 et cetera and manager responses were coded using Manager of Setting 1 and abbreviated to MS.1 et cetera. Assessment of the data allowed for coding into identifiable themes and patterns that are relevant to the research questions (Bryman, 2016). Themes represent a level of patterned response within the data and the richer the data the more likely a variety of themes and sub-themes will emerge (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Familiarisation with the data leads to the generation of codes followed by themes and sub-themes which are used for analysis and discussion. The analytical method used for the documentary analysis of the learning outcomes of the QQI Level 5 ECEC award is internal criticism where the document is subjected to rigorous analysis of its content (Bell, 2009).

3.7.1 Reflexivity.

Reflexivity refers to the process whereby the researcher reflects on their own biases, values and personal background and how this may influence their interaction with and interpretation of the study (Bryman, 2016; Creswell & Creswell, 2018). For this purpose, the first person will be used. I feel very strongly regarding the importance of providing high quality ECEC for young children that is adequately resourced and delivered by a highly qualified workforce. I have a working relationship with all the ECEC managers who took part in this research through my employment. For this reason, I was initially slightly apprehensive interviewing the managers as I was asking for information on their personal qualifications and experience. I feel this may have influenced how far I probed information in subsequent questioning in these instances. Due to my professional relationship with participants I was aware that they may be guarded when giving their responses. In these instances, I tried to gain more information with probing questions. As I feel so strongly about providing high quality ECEC for young children, I found it challenging when some managers stated that they believed a QQI Level 5 award was enough or not necessary to meet their needs.

For future research purposes, I feel that it would be necessary to be more prepared for my own beliefs and values on the research topic to be challenged by participants. In choosing a research sample in the future, I feel that it may be better to collect data from people with whom I have no prior relationship to allow for more neutrality in data collection.

3.8 Ethical Considerations

Denscombe (2017) outlines three key principles of research ethics. The interests of the participants should be protected, participation in the study should be voluntary and based on informed consent and the researcher should operate in an honest and open manner. This research complied with the ethical guidelines for research set out by TUD (2019). Participants were made aware of the purpose of the research and were assured of full confidentiality and anonymity and were assured that they have a right to withdraw at any time. This was made clear through the information letter and informed consent form.

Data collected from the interviews was encrypted, password protected, and stored on the researcher’s laptop along with a back-up in TUD’s secure cloud storage. This data was anonymised at source, used only for the purposes of this study, and not shared with any third parties. In line with TUD requirements, the data will be stored for a period of no more than seven years after the research has concluded after which all copies will be destroyed. If at any point during this time, any participant withdraws or otherwise wishes for their data to be destroyed this will be honoured.

3.9 Conclusion

This chapter has described and justified the interpretivist research design and the qualitative research method used in this study. It has outlined how the research sample was chosen along with the procedures used to ensure validity and reliability in data collection. The limitations of this research were detailed as was the method used for data analysis. Finally, the ethical considerations relevant to this research were discussed. The findings from this research are presented in the next chapter.

4 Chapter Four Findings

4.1 Introduction

The research questions of this study focus on investigating the perspectives of ECEC managers on the needs of young children, the implications of current qualification requirements for practitioners working with children under six years of age and the impact of current policy relating to working with young children. This chapter will present the main themes that emerged from the eight semi-structured interviews with nine managers of full day care settings and the documentary review of the learning outcomes of the QQI Level 5 ECEC award.

A profile of the settings is provided followed by a summary and description of the views of participants which are presented under three broad themes: needs of young children, qualifications and training and perspectives on policy and practice. Where participant responses are quoted, they are assigned a Manager of Setting Number (MS.X) to identify the source of the quote. Sub-themes will be explored under each of these categories where present.

4.2 Profile of Settings

Table 1

Profile of ECEC Settings

Table 1 above displays a profile of the ECEC settings who took part. The ECEC qualification level of the managers who took part ranged from QQI Level 5 to QQI Level 8. Across the settings there are a total of 503 children in attendance with 233 of these (46%) aged under two years and eight months. The majority of children in five of the settings are under three years of age. Seven of the settings cater for children from six months up to school going age. The remaining setting discontinued their provision for children under one year of age for financial reasons.

4.3 The Needs of Young Children

The central theme of the study, the nature of ECEC for young children, was explored in depth with each of the participants. Issues which emerged related to the developmental and sociocultural needs of young children, such as practical care, interactions, attachment and stimulation. These issues will now be presented in further detail.

All participants identified the basic, practical needs of young children, such as sleep, food and personal care as being the core of ECEC practice for this age group. When asked how they meet the more complex developmental and sociocultural needs of young children, participant responses ranged from building attachments, providing stimulation, supporting independence and offering choice, providing opportunities for physical development, ensuring positive interactions, providing consistency and respecting individuality.

“Making sure there’s a stimulating environment, that you’re following their needs, what they’re showing they’re interested in.” (MS.4).

“I would make reference to it regularly at my staff meetings, that the interactions are really, really important, and that you really shouldn’t stand quietly changing a child’s nappy.” (MS.3).

Attachment and interactions emerged as an even greater concern in community ECEC where families may experience greater vulnerability and stress.

“a lot of kind of behavioural issues that we have, a lot of it is attachment … some of the children that will be here, they never get a day off, they never get to stay at home with Mam or Dad and they need us.” (MS.7).

“you see the way they interact with the children, the way they speak to the children. Some parents speak to children like they’re grownups.” (MS.7).

While the findings suggest that participants are aware of the overall importance of the early years, three participants specifically described the nature of the first three years of a child’s life in developmental terms.

“all their neurons and everything … their brain is still kind of forming.” (MS.5).

“They are developing a lot more between that age group, it’s hourly almost.”. (MS.6).

“That’s when they form their everything, their bonds, social skills, their independence, their development … It’s huge. Zero to three is huge. I think people don’t realise that.” (MS.7).

4.4 Qualifications and Training

A key theme of the study, qualifications of the workforce, was discussed in depth with participants. All participants discussed their views on current qualification requirements, including the minimum QQI Level 5 award, initial training and how the ECCE programme impacts provision for young children.

4.4.1 Current qualification requirements.

Participant opinions were sought on the current qualification requirements for the ECEC sector. There were mixed responses relating to the introduction of a minimum qualification requirement at QQI Level 5.

“I think it’s great that there is a minimum qualification requirement. From the public’s perspective, we’re not just considered childminders.” (MS.3).

“I don’t think it’s enough in general … I just think having it as a minimum, it’s like, “I have that so now I don’t have to do anymore.”.” (MS.7).

The findings suggest that some participants would prefer if the minimum qualification requirement were higher.

“It should be a degree across the board.” (MS.5b).

However, the findings also demonstrate that several participants feel that higher qualification requirements are unjustified. Practitioner experience was seen as an important factor in meeting the needs of young children.

“I see the girls who are Level 5 and Level 6 trained and the way they stimulate the children … The girls who’ve done Level 8 and Level 7, are they any better? I don’t really think they are … I suppose would I take on somebody with Level 5 and 10 years’ experience or someone with Level 8 and no years’ experience, or two years’ experience … I would take on the experience first.” (MS.2).

“She has qualifications in life. She’s been with us 10 years.” (MS.8).

4.4.2 Initial training.

The views of participants on initial training of students at QQI Levels 5 and 6, specifically, the undertaking of placement were significantly represented across the findings. The findings suggest that most managers feel that initial training is inconsistent and does not prepare practitioners for working with young children.

“I’ve had people come to me, with childcare qualifications, who cannot change a nappy.” (MS.4).

“in a degree course, you have to do your placements from the first week. From day one you’re doing hands on experience instead of one day a week maybe once a month like some colleges, or some of them, you do them online, and then you just come in and they sort of think, “Oh yeah, I have my Level 6,” but they’ve never even been inside a room.” (MS.7).

“you have to feed the kids, you have to clean up after them, you have to do things like that … People come in and say, “They don’t teach that in college.”.” (MS.8).

The findings also demonstrate that while some managers feel that placement does not prepare ECEC students for working with young children, they are also reluctant to place students and newly qualified practitioners with the younger children specifically due to their lack of experience.

“they need people who are more experienced … I would be very wary hiring somebody out of college … While I would happily put them with three or four year olds … because a three and four year old can communicate.” (MS.6).

However, the current staffing crisis affecting the ECEC sector emerged as a significant finding which was discussed by six participants. One participant noted that this is forcing managers to place inexperienced, newly qualified practitioners with young children.

“all the people that work here that have a Level 5 … and they’re working a couple of years in childcare and then realise this isn’t for me. I’m financially never going to get a better wage than this, so why don’t I just go and work in a shop and get the same amount of money and with no stress and no 18 screaming kids … Then we get the newly qualified 19 year olds … We can’t put them in preschool. We have to put them in zero to three and it’s wrong.” (MS.6).

4.4.3 Qualification divide.

A total of 87 ECEC practitioners are employed across the settings with 56 of these working with young children and the remaining 31 working with the ECCE age group. Figure 1 shows the overall qualifications of all ECEC practitioners.

Figure 2 below illustrates that 63% of practitioners working with young children are qualified to QQI Level 5 and 7% have signed a grandfathering declaration. Reasons provided by managers for practitioners signing a grandfathering declaration included that practitioners were nearing retirement age and some practitioners refused to upskill.

“The other one just said no. “No way I’m going to go back to college. I’ll stay for as long as the grandfathering lets me and then I’ll just have to find another job.”.” (MS.6).

Figure 2 also shows that 16% of practitioners working with the older ECCE age group are qualified to QQI Level 5. There are no unqualified practitioners working with this age group and 45% of practitioners are qualified to degree level or higher.

Figure 2. Qualifications of practitioners working with young children and the ECCE age group.

4.4.4 QQI Level 5 and the young child.

Participant views were sought on whether they felt that the QQI Level 5 award enabled practitioners to meet the needs of young children. Eight managers stated that it does, however, they felt that the practitioner would need experience or the support of a more highly qualified practitioner or the manager. Two participants stated it is only suitable for an assistant in a room.

“I think even the ones without any qualification can meet the needs of the child if they have enough experience.” (MS.6).

The remaining participant does not believe that the QQI Level 5 award enables practitioners to meet the needs of young children.

“the staff here at Level 5, I think sometimes they struggle to meet the needs.” (MS.7).

This participant suggested that practitioners who have trained a number of years ago should be required to retrain. This was echoed by another participant, (MS.6), who believes that practitioners who have been qualified at QQI Level 5 or 6 for a number of years are less motivated in their day to day roles than their more highly qualified peers.

Findings from the documentary research to review the learning outcomes of the QQI Level 5 award demonstrate that there are four compulsory major components. The only detail specific to young children among these compulsory components is from the Child Health and Well Being component (QQI, 2019a) which relates to the nutritional and personal care needs of young children. The remaining modules where learning outcomes relate specifically to young children are minor components. When developing a QQI Level 5 award course, training bodies choose one of these minor components to deliver to learners. The learning outcomes specific to young children amongst these components relate to cardiac first response, respiratory emergencies, patterns of development from infancy to old age and again, the nutritional needs of young children.

There is, however, an Infant and Toddler Years minor component (QQI, 2019b). The purpose of this award is to provide learners with the “knowledge, skill and competence relevant to the theory and practice of the development, care and education of infants and toddlers” (QQI, 2019b, p. 1). The learning outcomes of this component relate to holistic development, principles of child development and the adult’s role in child development, the implications of neuroscience, policy and legislation relating to young children, fostering positive relationships, the benefits of play, planning environments and programmes of ECEC and evaluation of the adult’s role. The findings of this documentary research relating to the content of the Infant and Toddler Years minor component were not apparent in participant responses.

4.4.5 The ECCE programme.

The majority of participants noted that the introduction of the higher qualification requirements for the ECCE age group influences where they place more highly qualified practitioners.

“we haven’t … had that many degree staff … that would come through that would be put with younger age groups because … we wanted to have a higher cap.” (MS.5b).

One participant believes that the ECCE age group require more highly qualified practitioners as they are being prepared for primary school. This was linked to the view that the younger children require care rather than education. However, this view was countered by other participants who believe there is too much emphasis on the ECCE age group and that the younger age group would benefit from a higher qualification requirement.

“I think it will be better in babies … I just think it would nurture them more and give them better outcomes when they’re older.” (MS.5b).

“It’s all about the primary school, as if that’s the first step of your education. I think zero to three is so important, so important to put money in that, qualifications, minimum requirements … If you invest in that and there’s really good care … by the time they get to the ECCE, the child is so much more able to manage.”1 (MS.7).

4.5 Perspectives on Policy and Practice

Current ECEC policy and practice and how this impacts provision for young children was explored in depth with participants. Issues which emerged related to current regulatory requirements, parental leave and professional issues affecting the sector. These issues will now be presented in further detail

4.5.1 Regulatory requirements.

Group size and ratio requirements emerged as a noteworthy finding in providing quality ECEC for young children with participants preferring lower group sizes and ratios. “I don’t think you could ever have too many staff.” (MS.3).

“We have a baby room of six, and the staff can really get to know the children really well there. I know lots of places have baby rooms with up to 18 … I can’t imagine any other way that a group of 18 under ones would … produce a lot more stress for teams.” (MS.8).

The sleeping arrangement requirements under the Child Care Act 1991 (Early Years Services) Regulations 2016 were described by three participants as presenting challenges. One participant stated that if they were to open another setting, they would likely not provide ECEC for young children.

“it’s hard with the younger kids because you’ve got your sleep … If we ever thought about opening a separate place … we would then probably more go for something that’s like a preschool … It would be easier to meet the regulations.” (MS.1).

1The title of this research study emerged from this response.

4.5.2 Parental leave.

Seven of the eight settings take children from six months of age; however, the findings suggest that mothers are taking their full maternity and unpaid leave entitlements and where possible adding on extra leave to delay the starting age in ECEC. Linked to this finding is the opinion of some participants that children should not be in full day care and that parents should have the choice of staying at home with their young children.

“I don’t really think children under a year benefit terribly from being in a crèche … I just think that they should be at home with their mother … We’re only trying to replicate in this centre what parents would be doing at home.” (MS.2).

“I don’t think any child should be in full-time care … Some of those kids are in with us at 7.30am and they go home at 5.45pm in a group environment where they are not getting the amount of attention that they probably need.” (MS.4).

“I have to say … that to me is something that’s vitally important, that children should not be in full time day care. Why? Because they’re better off at home.” (MS.8).

4.5.3 Professional issues

Staffing issues, such as recognition for the role of the ECEC practitioner and job satisfaction were not specifically raised in the interview questions, however all participants discussed this area of practice as an existing concern. The findings suggest that the low status of the ECEC sector is due, in part, to the low qualification requirement which impacts on pay scales.

“If I can pay my staff more, I have staff that are really looking at a career as opposed to thinking what can they do next … That, in the long run, would directly affect the children.” (MS.1).

“our minimum requirement is Level 5. I mean like in any other sector that wouldn’t be acceptable. It wouldn’t … Most sectors need a minimum of a degree or a diploma or whatever. Childcare, FETAC Level 5. That to me says a lot about the industry, that’s all that’s needed.” (MS.7).

This low status extends to working with young children, with some participants reporting that the preference of practitioners is to work with the older age group. This is due to the higher capitation which allows managers to pay ECCE practitioners a higher wage.

The lack of a professional status was cited by one participant as being a barrier to engaging successfully with parents, who view the requests of the ECEC manager as less important than those of primary school teachers.

“a lot of the parents here if you ask them to do things they are like, “aw yeah yeah” but see with the primary schools, they’re like, “I have to go into the school,” because I think people view primary school as so important … the first stage of a child’s education.” (MS.7).

Connected to this lack of a professional status is the view of one participant that the role of the ECEC workforce is closely related to the role of mothers. This participant suggested the roll out of an apprenticeship scheme where unqualified people work in ECEC settings while obtaining a qualification. This was not echoed in other responses.

“Well I think if you’re a mother, you know the kind of problems that you have to deal with … you know when a child is starting to be sick … a mother without qualifications is very valuable with the younger ones.” (MS.8).

“if the minister really wants a good quality early years programme throughout Ireland, we do need to develop some form of apprenticeship and catch the mums maybe that are at home but are bored … and love children.” (MS.8).

The issue of job satisfaction emerged as a consistent concern across all eight interviews and was seen as an important precondition in meeting the needs of young children, despite the interview questions not seeking this information specifically. The findings show that when practitioners are satisfied in their role, they are likely to stay in the setting, therefore providing consistency for young children. Several participants cited the challenges associated with ECEC as impacting on job satisfaction.

“I think in childcare you definitely get burned out. Especially, when you’ve worked for years, and years and years in childcare. You’re just ground down over the years, you’re worn out. I can see that now. I’m starting to see it in the staff.” (MS.7).

“If you’ve got staff with maximum numbers for 10 hours a day, in every classroom in the building, they’re going to be under terrible stress.” (MS.8).

While manager’s perspectives were not specifically sought on their own leadership role, a number of barriers to providing pedagogical leadership emerged in the findings. These barriers related to a lack of time due to administration workload and staffing issues.

“there’s too much paperwork for us now. We’re taking away from our time with the kids … I do HR. I do the wages … Policies and procedures. Everything … Then you’re trying to cover if there’s a staff member sick. It’ll always be me who steps in to cover. I constantly feel I’m behind in paperwork.” (MS.4).

“the administration is a nightmare … We have an awful lot of work to do management wise even before the government schemes.” (MS.8).

4.5.4 Changes to policy.

When asked what changes to policy would benefit young children in ECEC, participant responses included extending maternity leave, providing seamless funding throughout ECEC to primary school, extending AIM and EYEI to include young children, reducing ratios and group sizes, increasing qualification requirements, introducing a salary scale and providing a higher capitation for practitioners working with young children.

“I think it should stay at 1:3, probably up to 18 months. They do require a lot of one on one.” (MS.5a).

“I think AIM … There’s been a couple of parents who have requested it because they’ve heard about it but it’s not available … I think it might just benefit a little bit more to have it for younger children.” (MS.5b).

“I would want the same higher capitation brought in for under threes.” (MS.6).

4.6 Conclusion

This chapter provided a detailed account of the key findings obtained from the data collection stage. Following a profile of the settings who took part in this research, findings were presented under the broad themes of the needs of young children, qualification and training issues and perspectives on policy and practice. These findings will be discussed further in the next chapter, considering the research questions and current literature.

5 Chapter Five Discussion and Conclusion

5.1 Introduction

This chapter will discuss the most significant findings that emerged from this research study in relation to the themes previously identified in the literature. These themes relate to how the needs of young children are perceived and addressed, the issue of qualifications and training, and the perspectives of managers on policy and practice. The findings will be discussed in relation to the literature highlighting commonalities and identifying differences. Recommendations drawn from the findings will be presented followed by a conclusion to this study

5.2 The Needs of Young Children

5.2.1 Developmental and sociocultural needs.